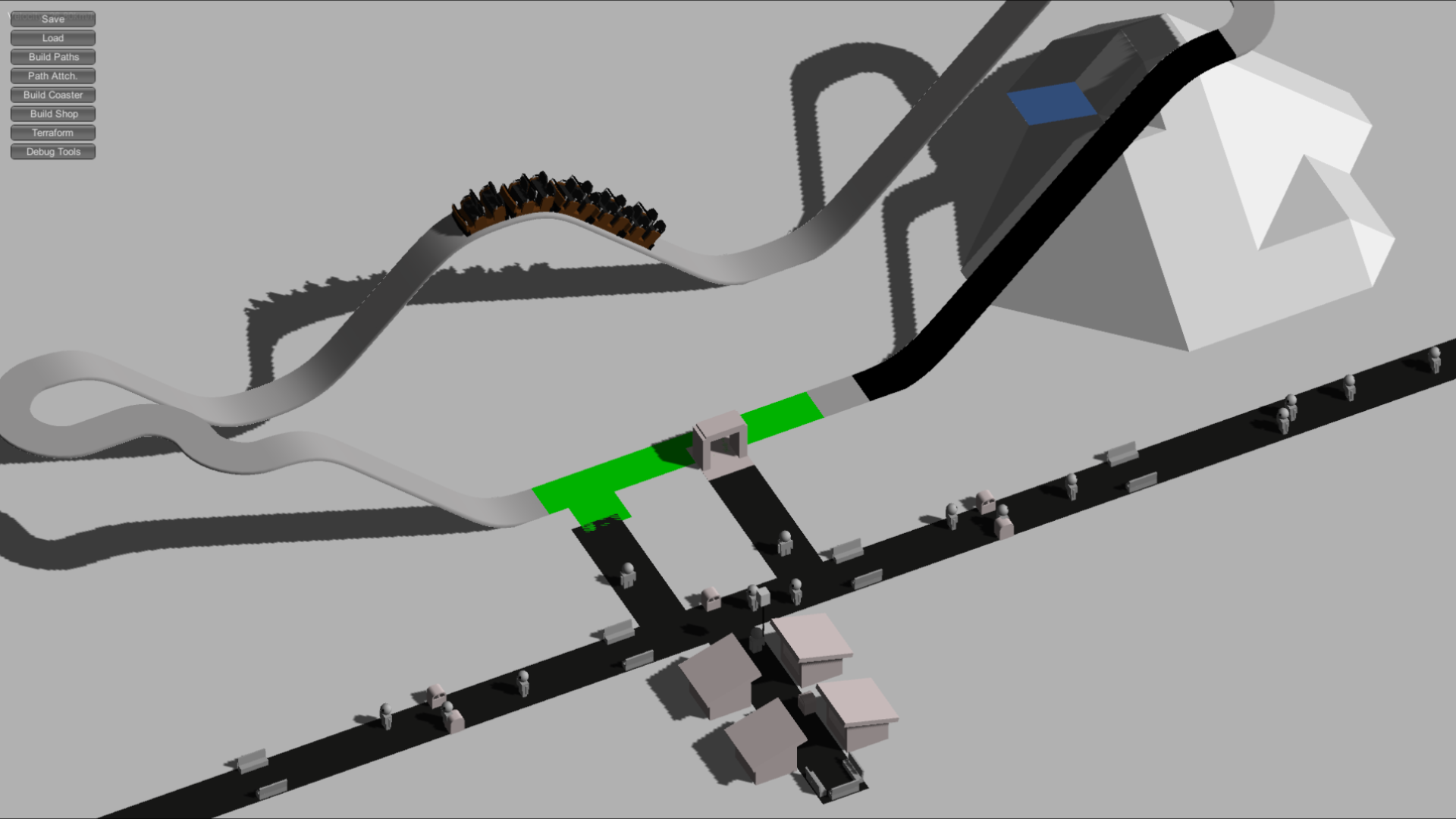

In preparation for Game Garden and in the time afterwards we've spent some time on polishing how placing objects works.

Placing objects is one of the main things you do in this game of course, so it needs to feel good and be intuitively understandable.

There's a few considerations we have to make for these tools. There are some restrictions we need to make simply due to how the game works, but generally we want to give players a lot of freedom so they can design their town however they want. At the same time we want everything to feel playful and easy to understand, and not like you're using some sort of 3D modeling software.

How fast you're able to get to a good looking result is also a very important consideration. We want players to be able to design a full house within a few minutes.

One basic tool that helps with this allows you to quickly duplicate any existing object:

Oftentimes this makes it unnecessary to search through the menus for the object that you're looking for, so this already speeds up building a lot.

Sometimes you just want to move an object. You could use the duplication tool to create a new object, then delete the old one... but simply picking up the object and moving it feels much nicer and better :)

And of course sometimes you just want to be able to go back a few steps, so there's undo.

Undo is one of the most-requested features for Parkitect. Unfortunately it's not something that can be added easily into a game that wasn't designed with undo in mind.

For Croakwood we knew that people would really want to have this, so we made sure to add support for this very early on.

We differentiate between two different types of objects, decorations and furniture.

Decorations are objects like plants, vases or crates and we allow players to place them very freely. They aren't locked to any grid and don't have any collision, so you can use them in a lot of creative ways.

Decorations can be rotated quite freely.

Furniture are objects that the villagers need to interact with, like chairs, tables or beds. Due to technical reasons furniture had to be locked to a grid and to 90° rotations so far.

Another nice side-effect is that this made furniture placement pretty quick due to the limited options, and we liked that figuring out how to fit all the required furniture into a house felt a bit like a small puzzle game.

Due to improvements we made to villager movement this year the technical limitations that required furniture to be on a grid do not exist anymore and we wondered... would it hurt to give a bit more freedom?

After giving it a try it's working quite well - the furniture still collides so your space is still limited, and the added freedom gives you more options for decorating the houses without adding significant complications. So we're keeping it like this for now :)

For some objects you can drag to create multiple of them in a row, and they can snap together automatically:

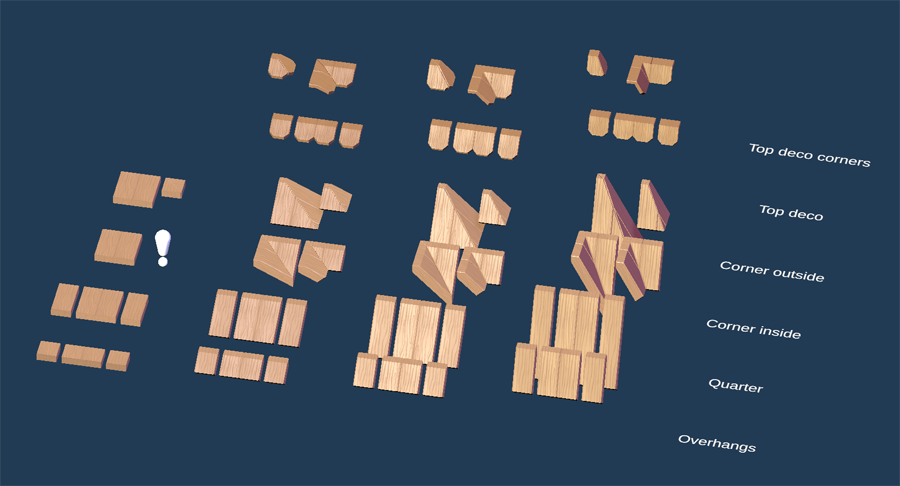

One case where it's not very fun to build something out of many individual tiles are roofs. They can have fairly complex shapes and there's a large number of pieces.

Having to piece these back together isn't very fun, so instead there's a tool that does it for you.

Getting this to work well took quite some time but it's pretty good finally :)